Introduction and Context

By the laws of the United States I am still a slave; and though I am now growing old, I might even yet be deemed of sufficient value to be worth pursuing as far as my present residence, if those to whom the law gives the right of dominion over my person and life, knew where to find me. For these reasons I have been advised, by those whom I believe to be my friends, not to disclose the true names of any of those families in which I was a slave, in Carolina or Georgia, lest this narrative should meet their eyes, and in some way lead them to a discovery of my retreat. - Charles Ball, Slavery in the United States, p. 136

|

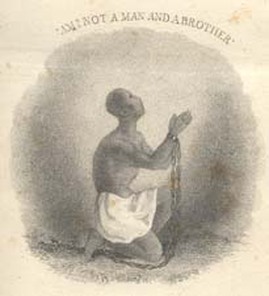

Charles Ball published his suspensful slave narrative in 1839, documenting a life with many traumatic and devastating personal losses. All told, Ball attempted escape from slavery four separate times, being recaptured on three of the occasions.

Ball was born into slavery towards the end of the 18th century and lived in Maryland with his mother and father until his mother was sold into slavery. Shortly following that, his father was also sold and made his escape before the purchase was finalized, making young Charles effectively an orphan. Charles Ball was sold to a succession of owners and separated from his first wife and child when he was sold to an owner in Georgia. At his second attempt to escape, Ball managed to reunite with his wife and live quietly as a refugee. When his wife died, he remarried and after twenty-two years of freedom and three more children, Ball was recaptured into slavery and sent back to Georgia. |

When Ball managed to successfully escape for a second time, he reached his home in Maryland to find that his wife and children, who were free by birth, had been kidnapped and enslaved. As the quote above indicates, Charles Ball lived out his existence after his second escape as inconspicuously as possible, but still maintained the ability to write about his experience in the institution. Considering the risk he had already taken, his bravery in writing and publishing his experiences is profound.

The text below describes an experience of Charles Ball witnessing the punishment of a slave on his plantation. Its vivid description reveals much about the harshness and inhumanity of the slave system. His text had such an impact on readers in America that in her famous tract, An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, Angelina Emily Grimke quoted Ball's work as a way to illustrate slave conditions. His original narrative was so popular that it was eventually republished in the 1850s under the title Fifty Years in Chains.

The text below describes an experience of Charles Ball witnessing the punishment of a slave on his plantation. Its vivid description reveals much about the harshness and inhumanity of the slave system. His text had such an impact on readers in America that in her famous tract, An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, Angelina Emily Grimke quoted Ball's work as a way to illustrate slave conditions. His original narrative was so popular that it was eventually republished in the 1850s under the title Fifty Years in Chains.

Document - from Slavery in the United States: A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, A Black Man

At the time I joined the company, the overseer was calling over the names of the whole, from a little book; and the first name that I heard was that of my companion whom I had just left, which was Lydia--called by him Lyd. As she did not answer, I said, "Master, Lydia, the woman that carries the baby on her back, will be here in a minute-- I left her just behind." The overseer took no notice of what I said, but went on with his roll-call.

As the people answered to their names, they passed off to the cabins, except three--two women and a man; who, when their names were called, were ordered to go into the yard, in front of the overseer's house. My name was the last on the list; and when it was called I was ordered into the yard with the three others. Just as we had entered, Lydia came up out of breath, with the child in her arms; and following us into the yard, dropped on her knees before the overseer, and begged him to forgive her. "Where have you been?" said he. Poor Lydia now burst into tears, and said, "I only stopped to talk awhile to this man," pointing to me; "but, indeed, master overseer, I will never, do so again." "Lie down," was his reply. Lydia immediately fell prostrate upon the ground and in this position he compelled her to remove her old tow linen shift, the only garment she wore, so as to expose her hips, when he gave her ten lashes, with his long whip, every touch of which brought blood, and a shriek from the sufferer. He then ordered her to go and get her supper, with an injunction never to stay behind again. The other three culprits were then put upon their trial.

The first was a middle aged woman, who had, as her overseer said, left several hills of cotton in the course of the day, without cleaning and hilling them in a proper manner. She received twelve lashes. The other two were charged in general terms, with having been lazy, and of having neglected their work that day. Each of these received twelve lashes.

These people all received punishment in the same manner that it had been inflicted upon Lydia, and when they were all gone, the overseer turned to me and said--"Boy, you are a stranger here yet, but I called you in, to let you see how things are done here, and to give you a little advice. When I get a new negro under my command, I never whip at first; I always give him a few days to learn his duty, unless he is an outrageous villain, in which case I anoint him a little at the beginning. I call over the names of all the hands twice every week, on Wednesday and Saturday evenings, and settle with them according to their general conduct, for the last three days. I call the names of my captains every morning, and it is their business to see that they have all their hands in their proper places. You ought not to have staid behind to-night with Lyd; but as this is your first offence, I shall overlook it, and you may go and get your supper." I made a low bow, and thanked master overseer for his kindness to me, and left him. This night for supper, we had corn bread and cucumbers; but we had neither salt, vinegar, nor pepper, with the cucumbers.

I had never before seen people flogged in the way our overseer flogged his people. This plan of making the person who is to be whipped, lie down upon the ground, was new to me, though it is much practised in the south; and I have since seen men and women too, cut nearly in pieces by this mode, of punishment. It has one advantage over tying people up by the hands, as it prevents all accidents from sprains in the thumbs or wrists. I have known people to hurt their joints very much, by struggling when tied up by the thumbs, or wrists, to undergo a severe whipping. The method of ground whipping, as it is called, is, in my opinion, very indecent, as it compels females to expose themselves in a very shameful manner.

The whip used by the overseers on the cotton plantations, is different from all other whips, that I have ever seen. The staff is about twenty or twenty-two inches in length, with a large and heavy head, which is often loaded with a quarter or half a pound of lead, wrapped in cat-gut, and securely fastened on, so that nothing but the greatest violence can separate it from the staff. The lash is ten feet long, made of small strips of buckskin, tanned so as to be dry and hard, and plaited carefully and closely together, of the thickness, in the largest part, of a man's little finger, but quite small at each extremity. At the farthest end of this thong is attached a cracker, nine inches in length, made of strong sewing silk, twisted and knotted, until it feels as firm as the hardest twine.

This whip, in an unpractised hand, is a very awkward and inefficient weapon; but the best qualification of the overseer of a cotton plantation is the ability of using this whip with adroitness; and when wielded by an experienced arm, it is one of the keenest instruments of torture ever invented by the ingenuity of man. The cat-o'-nine tails, used in the British military service, is but a clumsy instrument beside this whip; which has superseded the cow-hide, the hickory, and every other species of lash, on the cotton plantations. The cow-hide and hickory, bruise and mangle the flesh of the sufferer; but this whip cuts, when expertly applied, almost as keen as a knife, and never bruises the flesh, nor injures the bones....

(excerpt from Chapter 10, p. 158-162)

As the people answered to their names, they passed off to the cabins, except three--two women and a man; who, when their names were called, were ordered to go into the yard, in front of the overseer's house. My name was the last on the list; and when it was called I was ordered into the yard with the three others. Just as we had entered, Lydia came up out of breath, with the child in her arms; and following us into the yard, dropped on her knees before the overseer, and begged him to forgive her. "Where have you been?" said he. Poor Lydia now burst into tears, and said, "I only stopped to talk awhile to this man," pointing to me; "but, indeed, master overseer, I will never, do so again." "Lie down," was his reply. Lydia immediately fell prostrate upon the ground and in this position he compelled her to remove her old tow linen shift, the only garment she wore, so as to expose her hips, when he gave her ten lashes, with his long whip, every touch of which brought blood, and a shriek from the sufferer. He then ordered her to go and get her supper, with an injunction never to stay behind again. The other three culprits were then put upon their trial.

The first was a middle aged woman, who had, as her overseer said, left several hills of cotton in the course of the day, without cleaning and hilling them in a proper manner. She received twelve lashes. The other two were charged in general terms, with having been lazy, and of having neglected their work that day. Each of these received twelve lashes.

These people all received punishment in the same manner that it had been inflicted upon Lydia, and when they were all gone, the overseer turned to me and said--"Boy, you are a stranger here yet, but I called you in, to let you see how things are done here, and to give you a little advice. When I get a new negro under my command, I never whip at first; I always give him a few days to learn his duty, unless he is an outrageous villain, in which case I anoint him a little at the beginning. I call over the names of all the hands twice every week, on Wednesday and Saturday evenings, and settle with them according to their general conduct, for the last three days. I call the names of my captains every morning, and it is their business to see that they have all their hands in their proper places. You ought not to have staid behind to-night with Lyd; but as this is your first offence, I shall overlook it, and you may go and get your supper." I made a low bow, and thanked master overseer for his kindness to me, and left him. This night for supper, we had corn bread and cucumbers; but we had neither salt, vinegar, nor pepper, with the cucumbers.

I had never before seen people flogged in the way our overseer flogged his people. This plan of making the person who is to be whipped, lie down upon the ground, was new to me, though it is much practised in the south; and I have since seen men and women too, cut nearly in pieces by this mode, of punishment. It has one advantage over tying people up by the hands, as it prevents all accidents from sprains in the thumbs or wrists. I have known people to hurt their joints very much, by struggling when tied up by the thumbs, or wrists, to undergo a severe whipping. The method of ground whipping, as it is called, is, in my opinion, very indecent, as it compels females to expose themselves in a very shameful manner.

The whip used by the overseers on the cotton plantations, is different from all other whips, that I have ever seen. The staff is about twenty or twenty-two inches in length, with a large and heavy head, which is often loaded with a quarter or half a pound of lead, wrapped in cat-gut, and securely fastened on, so that nothing but the greatest violence can separate it from the staff. The lash is ten feet long, made of small strips of buckskin, tanned so as to be dry and hard, and plaited carefully and closely together, of the thickness, in the largest part, of a man's little finger, but quite small at each extremity. At the farthest end of this thong is attached a cracker, nine inches in length, made of strong sewing silk, twisted and knotted, until it feels as firm as the hardest twine.

This whip, in an unpractised hand, is a very awkward and inefficient weapon; but the best qualification of the overseer of a cotton plantation is the ability of using this whip with adroitness; and when wielded by an experienced arm, it is one of the keenest instruments of torture ever invented by the ingenuity of man. The cat-o'-nine tails, used in the British military service, is but a clumsy instrument beside this whip; which has superseded the cow-hide, the hickory, and every other species of lash, on the cotton plantations. The cow-hide and hickory, bruise and mangle the flesh of the sufferer; but this whip cuts, when expertly applied, almost as keen as a knife, and never bruises the flesh, nor injures the bones....

(excerpt from Chapter 10, p. 158-162)

Document Comparison - excerpt from An Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, Angelina Emily Grimke

|

"This whip, in an unpractised hand, is a very awkward and inefficient weapon; but the best qualification of the overseer of a cotton plantation is the ability of using this whip with adroitness; and when wielded by an experienced arm, it is one of the keenest instruments of torture ever invented by the ingenuity of man. The cat-o'-nine- tails, used in the British military service, is but a clumsy instrument beside this whip, which has superseded the cowhide, the hickory, and every other species of lash on the cotton plantations. The cowhide and the hickory bruise and mangle the flesh of the sufferer; but this whip cuts, when expertly applied, almost as keen as a knife, and never bruises the flesh nor injures the bones." What then do our sisters say to using cotton which is raised under the keen and cutting lash of this whip, by the mancipated mothers, wives and daughters of the South? Can these sufferers really believe we are remembering them that are in bonds as bound with them, whilst we freely use what costs them so much agony?

|

Questions for Discussion and Document Based Analysis

- Based on the text, why did Lydia receive a punishment?

- In the text, how does Ball describe that the whipping in the South is different than the whipping that he has experienced?

- How does Angelina Emily Grimke use Charles Ball's Narrative to make an argument for the duty of her "sisters" (Northern white women)?

- What words does Grimke italicize from Ball's account? Why do you think she chooses these particular words to emphasize?

- What does the appearance of Ball's text in Grimke's pamphlet reveal?

Sources Referenced

James Basker, ed, American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation, (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2012), 325.

"Charles Ball's Narrative: Fifty Years in Chains," Public Broadcasting System: Africans in America, Accessed on October 28, 2014.

"Charles Ball's Narrative: Fifty Years in Chains," Public Broadcasting System: Africans in America, Accessed on October 28, 2014.