Introduction and Context

TO WELLS BROWN, OF OHIO.

THIRTEEN years ago, I came to your door, a weary fugitive from chains and stripes. I was a stranger, and you took me in. I was hungry, and you fed me. Naked was I, and you clothed me. Even a name by which to be known among men, slavery had denied me. You bestowed upon me your own. Base indeed should I be, if I ever forget what I owe to you, or do anything to disgrace that honored name!

As a slight testimony of my gratitude to my earliest benefactor, I take the liberty to inscribe to you this little Narrative of the sufferings from which I was fleeing when you had compassion upon me. In the multitude that you have succored, it is very possible that you may not remember me; but until I forget God and myself, I can never forget you.

Your grateful friend,

WILLIAM WELLS BROWN

|

Born on a plantation near Lexington, Kentucky in 1814, William Wells Brown was the son of a white man and a slave woman. Brown lived mostly around St. Louis, Missouri until the age of twenty and was exposed to and experienced slavery around varied conditions. The master later moved close to St. Louis. Brown and his mother were frequently hired out in the city. For a time, Brown worked with the antislavery newspaper editor and publisher Elijah P. Lovejoy. Lovejoy was later and famously killed by a pro-slavery mob in Alton, Illinois.

Much of Brown's young life was spent on steamboats traveling the Mississippi, where he witnessed countless occasions of slaves being sold, traded, and abused. On his second attempt, Brown was able to escape to freedom in 1834 with the help of abolitionist Wells Brown (from whom William Brown adopted his name). For the next nine years, Brown worked aboard a Lake Erie steamboat while also acting as an Underground Railroad conductor in Buffalo, New York. Brown moved to Boston where he undertook his very successful literary career publishing his narrative and other books including his controversial novel, Clotel; or, The President's Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States. This book is the first novel published by an African American, inspired by Thomas Jefferson's infamous affair with his slave, Sally Hemings. |

In his scholarly work, Stephen Lucasi points out that while Brown's testimony included many of the similar components of other narratives of the day, Brown notably left out the mention of his acquisition of literacy. This is significant because Brown pointed to other means of procuring his freedom than reading or writing -travel. As a result, Brown's narrative went outside the conventions of most slave narratives of the day, being simultaneously a slave narrative and a travel narrative. The following passage talks about Brown's journey to New Orleans with his master where they sold slaves at the market.

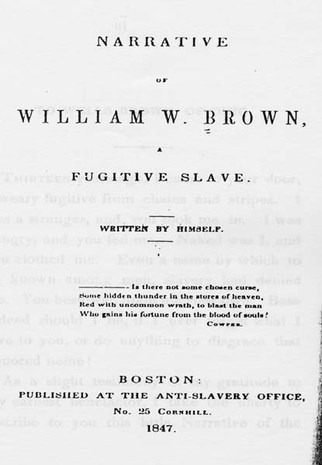

Document - Narrative of William W. Brown, a fugitive slave. Written by Himself

In a few days we reached New Orleans, and arriving there in the night, remained on board until morning. While at New Orleans this time, I saw a slave killed; an account of which has been published by Theodore D. Weld, in his book entitled, "Slavery as it is." The circumstances were as follows. In the evening, between seven and eight o'clock, a slave came running down the levee, followed by several men and boys. The whites were crying out, "Stop that negro; stop that negro*;" while the poor panting slave, in almost breathless accents, was repeating, "I did not steal the meat--I did not steal the meat." The poor man at last took refuge in the river. The whites who were in pursuit of him, run on board of one of the boats to see if they could discover him. They finally espied him under the bow of the steamboat Trenton. They got a pike-pole, and tried to drive him from his hiding place. When they would strike at him, he would dive under the water. The water was so cold, that it soon became evident that he must come out or be drowned.

While they were trying to drive him from under the bow of the boat or drown him, he would in broken and imploring accents say, "I did not steal the meat; I did not steal the meat. My master lives up the river. I want to see my master did not steal the meat. Do let me go home to master." After punching him, and striking him over the head for some time, he at last sunk in the water, to rise no more alive.

On the end of the pike-pole with which they were striking him was a hook which caught in his clothing, and they hauled him up on the bow of the boat. Some said he was dead, others said he was "playing possum," while others kicked him to make him get up, but it was of no use--he was dead.

As soon as they became satisfied of this, they commenced leaving, one after another. One of the hands on the boat informed the captain that they had killed the man, and that the dead body was lying on the deck. The captain came on deck, and said to those who were remaining, "You have killed this negro*; now take him off of my boat." The captain's name was Hart. The dead body was dragged on shore and left there. I went on board of the boat where our gang of slaves were, and during the whole night my mind was occupied with what I had seen. Early in the morning, I went on shore to see if the dead body remained there. I found it in the same position that it was left the night before. I watched to see what they would do with it. It was left there until between eight and nine o'clock, when a cart, which takes up the trash out of the streets, came along, and the body was thrown in, and in a few minutes more was covered over with dirt which they were removing from the streets. During the whole time, I did not see more than six or seven persons around it, who, from their manner, evidently regarded it as no uncommon occurrence.

During our stay in the city, I met with a young white man with whom I was well acquainted in St. Louis. He had been sold into slavery, under the following circumstances. His father was a drunkard, and very poor, with a family of five or six children. The father died, and left the mother to take care of and provide for the children as best she might. The eldest was a boy, named Burrill, about thirteen years of age, who did chores in a store kept by Mr. Riley, to assist his mother in procuring a living for the family. After working with him two years, Mr. Riley took him to New Orleans to wait on him while in that city on a visit, and when he returned to St. Louis, he told the mother of the boy that he had died with the yellow fever. Nothing more was heard from him, no one supposing him to be alive. I was much astonished when Burrill told me his story. Though I sympathized with him, I could not assist him. We were both slaves. He was poor, uneducated, and without friends; and if living, is, I presume, still held as a slave.

After selling out this cargo of human flesh, we returned to St. Louis, and my time was up with Mr. Walker. I had served him one year, and it was the longest year I ever lived.

(from Chapter 7, p. 59-62)

While they were trying to drive him from under the bow of the boat or drown him, he would in broken and imploring accents say, "I did not steal the meat; I did not steal the meat. My master lives up the river. I want to see my master did not steal the meat. Do let me go home to master." After punching him, and striking him over the head for some time, he at last sunk in the water, to rise no more alive.

On the end of the pike-pole with which they were striking him was a hook which caught in his clothing, and they hauled him up on the bow of the boat. Some said he was dead, others said he was "playing possum," while others kicked him to make him get up, but it was of no use--he was dead.

As soon as they became satisfied of this, they commenced leaving, one after another. One of the hands on the boat informed the captain that they had killed the man, and that the dead body was lying on the deck. The captain came on deck, and said to those who were remaining, "You have killed this negro*; now take him off of my boat." The captain's name was Hart. The dead body was dragged on shore and left there. I went on board of the boat where our gang of slaves were, and during the whole night my mind was occupied with what I had seen. Early in the morning, I went on shore to see if the dead body remained there. I found it in the same position that it was left the night before. I watched to see what they would do with it. It was left there until between eight and nine o'clock, when a cart, which takes up the trash out of the streets, came along, and the body was thrown in, and in a few minutes more was covered over with dirt which they were removing from the streets. During the whole time, I did not see more than six or seven persons around it, who, from their manner, evidently regarded it as no uncommon occurrence.

During our stay in the city, I met with a young white man with whom I was well acquainted in St. Louis. He had been sold into slavery, under the following circumstances. His father was a drunkard, and very poor, with a family of five or six children. The father died, and left the mother to take care of and provide for the children as best she might. The eldest was a boy, named Burrill, about thirteen years of age, who did chores in a store kept by Mr. Riley, to assist his mother in procuring a living for the family. After working with him two years, Mr. Riley took him to New Orleans to wait on him while in that city on a visit, and when he returned to St. Louis, he told the mother of the boy that he had died with the yellow fever. Nothing more was heard from him, no one supposing him to be alive. I was much astonished when Burrill told me his story. Though I sympathized with him, I could not assist him. We were both slaves. He was poor, uneducated, and without friends; and if living, is, I presume, still held as a slave.

After selling out this cargo of human flesh, we returned to St. Louis, and my time was up with Mr. Walker. I had served him one year, and it was the longest year I ever lived.

(from Chapter 7, p. 59-62)

Letter referring to William Brown's Narrative

DEDHAM July 1, 1847.

To WILLIAM W. BROWN.

MY DEAR FRIEND :—I heartily thank you for the privilege of reading the manuscript of your Narrative. I have read it with deep and strong emotion. I am much mistaken if it be not greatly successful and eminently useful. It presents a different phase of the infernal slave-system from that portrayed in the admirable story of Mr. Douglass, and gives us a glimpse of its hideous cruelties in other portions of its domain.

Your opportunities of observing the workings of this accursed system have been singularly great. Your experiences in the Field, in the House, and especially on the River in the service of the slave-trader, Walker, have been such as few individuals have had;—no one, certainly, who has been competent to describe them. What I have admired, and marvelled at, in your Narrative, is the simplicity and calmness with which you describe scenes and actions which might well 'move the very stones to rise and mutiny' against the National Institution which makes them possible.

You will perceive that I have made very sparing use of your flattering permission to alter what you had written. To correct a few errors, which appeared to be merely clerical ones, committed in the hurry of composition, under unfavorable circumstances, and to suggest a few curtailments, is all that I have ventured to do. I should be a bold man as well as vain one, if I should attempt to improve your descriptions of what you have seen and suffered. Some of the scenes are not unworthy of De Foe himself.

I trust and believe that your Narrative will have a wide circulation. I am sure it deserves it. At least, a man must be differently constituted from me, who can rise from the perusal of your Narrative without feeling that he understands slavery better, and hates it worse, than he ever did before.

I am, very faithfully, and respectfully,

Your friend,

EDMUND QUINCY

To WILLIAM W. BROWN.

MY DEAR FRIEND :—I heartily thank you for the privilege of reading the manuscript of your Narrative. I have read it with deep and strong emotion. I am much mistaken if it be not greatly successful and eminently useful. It presents a different phase of the infernal slave-system from that portrayed in the admirable story of Mr. Douglass, and gives us a glimpse of its hideous cruelties in other portions of its domain.

Your opportunities of observing the workings of this accursed system have been singularly great. Your experiences in the Field, in the House, and especially on the River in the service of the slave-trader, Walker, have been such as few individuals have had;—no one, certainly, who has been competent to describe them. What I have admired, and marvelled at, in your Narrative, is the simplicity and calmness with which you describe scenes and actions which might well 'move the very stones to rise and mutiny' against the National Institution which makes them possible.

You will perceive that I have made very sparing use of your flattering permission to alter what you had written. To correct a few errors, which appeared to be merely clerical ones, committed in the hurry of composition, under unfavorable circumstances, and to suggest a few curtailments, is all that I have ventured to do. I should be a bold man as well as vain one, if I should attempt to improve your descriptions of what you have seen and suffered. Some of the scenes are not unworthy of De Foe himself.

I trust and believe that your Narrative will have a wide circulation. I am sure it deserves it. At least, a man must be differently constituted from me, who can rise from the perusal of your Narrative without feeling that he understands slavery better, and hates it worse, than he ever did before.

I am, very faithfully, and respectfully,

Your friend,

EDMUND QUINCY

Questions for Discussion and Document Based Analysis

- William W. Brown explains a situation where he saw a slave killed. Why was the slave killed and who killed him?

- What happened to Brown's friend, Burrill?

- At the end of this passage, Brown explained that his year with Walker was the "longest year I ever lived." Based on what you have read, why do you think that Brown says this?

Sources Referenced

James Basker, ed, American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation, (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2012), 491.

Stephen Lucasi, "William Wells Brown's "Narrative" & Traveling Subjectivity," African American Review, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall, 2007): 521-539.

Mary Alice Kirkpatrick, "Summary of the Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave. Written by Himself," Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004.

Stephen Lucasi, "William Wells Brown's "Narrative" & Traveling Subjectivity," African American Review, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall, 2007): 521-539.

Mary Alice Kirkpatrick, "Summary of the Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave. Written by Himself," Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004.