Introduction and Context

"Ten years I toiled for that man without reward. Ten years of my incessant labor has contributed to increase the bulk of his possessions. Ten years I was compelled to address him with down-cast eyes and uncovered head—in the attitude and language of a slave. I am indebted to him for nothing, save undeserved abuse and stripes. Beyond the reach of his inhuman thong, and standing on the soil of the free State where I was born, thanks be to Heaven, I can raise my head once more among men. I can speak of the wrongs I have suffered, and of those who inflicted them, with upraised eyes." - Solomon Northup about his master, Edwin Epps, p. 183

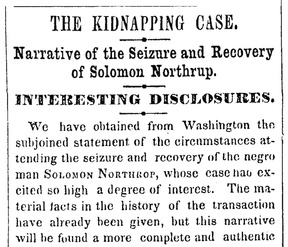

Solomon Northup's fascinating and heart-wrenching testimony has earned renewed attention due to the production of the Oscar Award Winning 2013 film, "!2 Years a Slave."

Solomon Northup was born a free man in 1808 in upstate New York. As a young man, Northup helped his father with farming chores and worked as a raftsman on the waterways of upstate New York. During the 1830s after he had married and fathered three children, Northup became locally renowned and employed as an excellent violinist.

In 1841, Northup received an offer to perform for a traveling music job from two men. Soon after he accepted, they drugged him and sold him into slavery at an auction in New Orleans. Northup was bought and sold a number of times and changed hands of slaveowners several times. In some instances, he was treated well but he also experienced great cruelty at the hands of Mr. Edwin Epps, his master for the longest period.

Solomon Northup was born a free man in 1808 in upstate New York. As a young man, Northup helped his father with farming chores and worked as a raftsman on the waterways of upstate New York. During the 1830s after he had married and fathered three children, Northup became locally renowned and employed as an excellent violinist.

In 1841, Northup received an offer to perform for a traveling music job from two men. Soon after he accepted, they drugged him and sold him into slavery at an auction in New Orleans. Northup was bought and sold a number of times and changed hands of slaveowners several times. In some instances, he was treated well but he also experienced great cruelty at the hands of Mr. Edwin Epps, his master for the longest period.

|

After years of bondage, Northup got into contact with an abolitionist from Canada, who sent letters to notify Northup's family of his whereabouts. Upon the discovery, an official state agent was sent to Louisiana to reclaim Northup, leading to his rescue from slavery. The narrative was recorded by David Wilson, a white lawyer and legislator from New York. His claims in the preface of the book indicate a truthful dictation. The book was dedicated to Harriet Beecher Stowe and introduced as "another Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin," which had been recently published. Northup's narrative was published in 1853, shortly after he was liberated. It sold over thirty thousand copies, becoming one of the best-selling slave narratives of its time. |

The following passage is the account of a period in time when Northup and a fellow bondsman planned a mutiny on the ship they were on while traveling to New Orleans to be sold. The despondency of Northup is apparent in the passage as are the overwhelming odds against him.

Document - from Solomon Northup's Twelve Years a Slave

Towards evening, on the first day of the calm, Arthur and myself were in the bow of the vessel, seated on the windlass. We were conversing together of the probable destiny that awaited us, and mourning together over our misfortunes. Arthur said, and I agreed with him, that death was far less terrible than the living prospect that was before us. For a long time we talked of our children, our past lives, and of the probabilities of escape. Obtaining possession of the brig was suggested by one of us.

We discussed the possibility of our being able, in such an event, to make our way to the harbor of New-York. I knew little of the compass; but the idea of risking the experiment was eagerly entertained. The chances, for and against us, in an encounter with the crew, was canvassed. Who could be relied upon, and who could not, the proper time and manner of the attack, were all talked over and over again. From the moment the plot suggested itself I began to hope. I revolved it constantly in my mind. As difficulty after difficulty arose, some ready conceit was at hand, demonstrating how it could be overcome. While others slept, Arthur and I were maturing, our plans. At length, with much caution, Robert was gradually made acquainted with our intentions. He approved of them at once, and entered into the conspiracy with a zealous spirit. There was not another slave we dared to trust. Brought up in fear and ignorance as they are, it can scarcely be conceived how servilely they will cringe before a white man's look. It was not safe to deposit so bold a secret with any of them, and finally we three resolved to take upon ourselves alone the fearful responsibility of the attempt.

At night, as has been said, we were driven into the hold, and the hatch barred down. How to reach the deck was the first difficulty that presented itself. On the bow of the brig, however I had observed the small boat lying bottom upwards. It occurred to me that by secreting ourselves underneath it, we would not be missed from the crowd, as they were hurried down into the hold at night. I was selected to make the experiment, in order to satisfy ourselves of its feasibility. The next evening, accordingly, after supper, watching my opportunity, I hastily concealed myself beneath it. Lying close upon the deck, I could see what was going on around me, while wholly unperceived myself In the morning, as they came up, I slipped from my hiding place without being observed. The result was entirely satisfactory.

The captain and mate slept in the cabin of the former. From Robert, who had frequent occasion, in his capacity of waiter, to make observations in that quarter we ascertained the exact position of their respective berths. He further informed us that there were always two pistols and a cutlass lying on the table. The crew's cook slept in the cook galley on deck, a sort of vehicle on wheels, that could be moved about as convenience required, while the sailors, numbering only six, either slept in the forecastle, or in hammocks swung among the rigging.

Finally our arrangements were all completed. Arthur and I were to steal silently to the captain's cabin, seize the pistols and cutlass, and as quickly as possible despatch him and the mate. Robert, with a club, was to stand by the door leading from the deck down into the cabin, and, in case of necessity, beat back the sailors, until we could hurry to his assistance. We were to proceed then as circumstances might require. Should the attack be so sudden and successful as to prevent resistance, the hatch was to remain barred down; otherwise the slaves were to be called up, and in the crowd, d, and hurry, and confusion of the time, we resolved to regain our liberty or lose our lives. I was then to assume the unaccustomed place of pilot, and, steering northward, we trusted that some lucky wind might bear us to the soil of freedom.

The mate's name was Biddee, the captain's I cannot now recall, though I rarely ever forget a name once heard. The captain was a small, genteel man, erect and prompt, with a proud bearing, and looked the personification of courage. If he is still living, and these pages should chance to meet his eye, hewill learn a fact connected with the voyage of the brig, from Richmond to New-Orleans, in 1841, not entered on his log-book.

We were all prepared, and impatiently waiting an opportunity of putting our designs into execution, when they were frustrated by a sad and unforeseen event. Robert was taken ill. It was soon announced that he had the small-pox. He continued to grow worse, and four days previous to our arrival in New-Orleans he died. One of the sailors sewed him in his blanket, with a large stone from the ballast at his feet, and then laying him on a hatchway, and elevating it with tackles above the railing, the inanimate body of poor Robert was consigned to the white waters of the gulf.

We were all panic-stricken by the appearance of the small-pox. The captain ordered lime to be scattered through the hold, and other prudent precautions to be taken. The death of Robert, however, and the presence of the malady, oppressed me sadly, and I gazed out over the great waste of waters with a spirit that was indeed disconsolate.

An evening or two after Robert's burial, I was leaning on the hatchway near the forecastle, full of desponding thoughts, when a sailor in a kind voice asked me why I was so down-hearted. The tone and manner of the man assured me, and I answered, because I was a freeman, and had been kidnapped. He remarked that it was enough to make any one down-hearted, and continued to interrogate me until he learned the particulars of my whole history...

(excerpt from p. 69-73)

We discussed the possibility of our being able, in such an event, to make our way to the harbor of New-York. I knew little of the compass; but the idea of risking the experiment was eagerly entertained. The chances, for and against us, in an encounter with the crew, was canvassed. Who could be relied upon, and who could not, the proper time and manner of the attack, were all talked over and over again. From the moment the plot suggested itself I began to hope. I revolved it constantly in my mind. As difficulty after difficulty arose, some ready conceit was at hand, demonstrating how it could be overcome. While others slept, Arthur and I were maturing, our plans. At length, with much caution, Robert was gradually made acquainted with our intentions. He approved of them at once, and entered into the conspiracy with a zealous spirit. There was not another slave we dared to trust. Brought up in fear and ignorance as they are, it can scarcely be conceived how servilely they will cringe before a white man's look. It was not safe to deposit so bold a secret with any of them, and finally we three resolved to take upon ourselves alone the fearful responsibility of the attempt.

At night, as has been said, we were driven into the hold, and the hatch barred down. How to reach the deck was the first difficulty that presented itself. On the bow of the brig, however I had observed the small boat lying bottom upwards. It occurred to me that by secreting ourselves underneath it, we would not be missed from the crowd, as they were hurried down into the hold at night. I was selected to make the experiment, in order to satisfy ourselves of its feasibility. The next evening, accordingly, after supper, watching my opportunity, I hastily concealed myself beneath it. Lying close upon the deck, I could see what was going on around me, while wholly unperceived myself In the morning, as they came up, I slipped from my hiding place without being observed. The result was entirely satisfactory.

The captain and mate slept in the cabin of the former. From Robert, who had frequent occasion, in his capacity of waiter, to make observations in that quarter we ascertained the exact position of their respective berths. He further informed us that there were always two pistols and a cutlass lying on the table. The crew's cook slept in the cook galley on deck, a sort of vehicle on wheels, that could be moved about as convenience required, while the sailors, numbering only six, either slept in the forecastle, or in hammocks swung among the rigging.

Finally our arrangements were all completed. Arthur and I were to steal silently to the captain's cabin, seize the pistols and cutlass, and as quickly as possible despatch him and the mate. Robert, with a club, was to stand by the door leading from the deck down into the cabin, and, in case of necessity, beat back the sailors, until we could hurry to his assistance. We were to proceed then as circumstances might require. Should the attack be so sudden and successful as to prevent resistance, the hatch was to remain barred down; otherwise the slaves were to be called up, and in the crowd, d, and hurry, and confusion of the time, we resolved to regain our liberty or lose our lives. I was then to assume the unaccustomed place of pilot, and, steering northward, we trusted that some lucky wind might bear us to the soil of freedom.

The mate's name was Biddee, the captain's I cannot now recall, though I rarely ever forget a name once heard. The captain was a small, genteel man, erect and prompt, with a proud bearing, and looked the personification of courage. If he is still living, and these pages should chance to meet his eye, hewill learn a fact connected with the voyage of the brig, from Richmond to New-Orleans, in 1841, not entered on his log-book.

We were all prepared, and impatiently waiting an opportunity of putting our designs into execution, when they were frustrated by a sad and unforeseen event. Robert was taken ill. It was soon announced that he had the small-pox. He continued to grow worse, and four days previous to our arrival in New-Orleans he died. One of the sailors sewed him in his blanket, with a large stone from the ballast at his feet, and then laying him on a hatchway, and elevating it with tackles above the railing, the inanimate body of poor Robert was consigned to the white waters of the gulf.

We were all panic-stricken by the appearance of the small-pox. The captain ordered lime to be scattered through the hold, and other prudent precautions to be taken. The death of Robert, however, and the presence of the malady, oppressed me sadly, and I gazed out over the great waste of waters with a spirit that was indeed disconsolate.

An evening or two after Robert's burial, I was leaning on the hatchway near the forecastle, full of desponding thoughts, when a sailor in a kind voice asked me why I was so down-hearted. The tone and manner of the man assured me, and I answered, because I was a freeman, and had been kidnapped. He remarked that it was enough to make any one down-hearted, and continued to interrogate me until he learned the particulars of my whole history...

(excerpt from p. 69-73)

12 Years a Slave, the Oscar-Award Winning Film

|

The screenwriter of the film sought to bring back to the public memory the reality of the slave experience, something that has fallen out of the public memory.

"We have to remember, when Solomon wrote his memoir, at that time, this was a best-seller. It became a linchpin in the abolitionist cause. He toured, he spoke. And the story fell into obscurity. And we're having these conversations now, and what people are walking away from this film and this story with is that ... really didn't have any concept of what slavery was all about." - John Ridley, Screenwriter for "12 Years a Slave" |

|

Questions for Discussion and Document Based Analysis

- What are the pros and cons weighed by Solomon Northup on deciding to try to overthrow the ship?

- Cite what happens to ruin the plan of Northup and the other slaves?

- Based on the story, what do you think the word disconsolate means in this context?

- Explain why Solomon Northup would make the literary decision to include this story in such detail.

Sources Referenced

James Basker, ed., American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation, New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2012: 662.

Robert Brent Toplin, "Making a Slavery Docudrama," OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 1, No. 2, Teaching about Slavery (Fall, 1985): 17-19.

Joseph Stromburg, The New York Times' 1853 Coverage of Solomon Northup, the Hero of "12 Years A Slave," Smithsonian Magazine, March 3, 2014.

Robert Brent Toplin, "Making a Slavery Docudrama," OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 1, No. 2, Teaching about Slavery (Fall, 1985): 17-19.

Joseph Stromburg, The New York Times' 1853 Coverage of Solomon Northup, the Hero of "12 Years A Slave," Smithsonian Magazine, March 3, 2014.