Introduction and Context

|

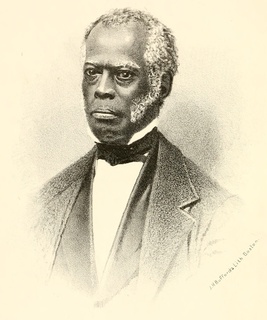

Lunsford Lane's story is important to the genre of the slave narrative because it outlined the lawful barriers that were in place for African Americans during the antebellum period. Lane was a contributing worker in society and worked extremely hard to earn the rights that were otherwise naturally enjoyed by white families during this time. His experience was a testimony towards the necessity for skill and perseverance in freed slaves as well as the constant struggle for survival, even upon legal freedom. Throughout his narrative, Lane meticulously documented the bills of sale, letters, and texts of the laws that give credibility and authority to his experiences and roadblocks.

The slave narrative of Lunsford Lane is an incredible story of entrepreneurship and efficacy in the face of overwhelming odds. Lane was born in North Carolina in 1803 and gained a skill for business by the time he was a teenager. He managed to invent, produce, and sell tobacco pipes to the extent that over time he was able to purchase his freedom. |

While his freedom was cause for much excitement, Lane desired to also purchase the freedom of his wife and children for $2500 (a huge sum in this time period). Lane encountered tremendous complications in the eight-year journey to procure emancipation for the rest of his family. For example, a North Carolina law that barred free blacks from entering or residing in the state increased the difficulty of purchasing his wife and children.

Because of this law, Lane was forced to move out of North Carolina. He eventually settled into Boston where he raised money by speaking at anti-slavery meetings. After almost two years, he raised enough to start the process of freeing his family. During his trip back to Raleigh, Lane met further hardship in procuring his family's manumission. The passage below describes the details of Lane's harrowing adventure to reunite with his family and his near death experience that resulted.

Because of this law, Lane was forced to move out of North Carolina. He eventually settled into Boston where he raised money by speaking at anti-slavery meetings. After almost two years, he raised enough to start the process of freeing his family. During his trip back to Raleigh, Lane met further hardship in procuring his family's manumission. The passage below describes the details of Lane's harrowing adventure to reunite with his family and his near death experience that resulted.

Document - excerpt from The Narrative of Lunsford Lane, Formerly of Raleigh, N.C.

...I need not say, what the reader has already seen, that my life so far had been one of joy succeeding sorrow, and sorrow following joy; of hope, of despair, of bright prospects, of gloom; and of as many hues as ever appear on the varied sky, from the black of midnight, or the deep brown of a tempest, to the bright warm glow of a clear noon day.

On the 11th of April, it was noon with me; I left Boston on my way for Raleigh with high hopes, intending to pay over the money for my family and return with them to Boston, which I designed should be my future home; for there I had found friends, and there I would find a grave... I thought, too, that the assurances I had received from the Governor, through Mr. Smith, and the assurances of other friends, were a sufficient guaranty that I might visit the home of my boyhood, of my youth, of my manhood, in peace, especially as I was to stay but for a few days and then to return. With these thoughts, and with the thoughts of my family and freedom, I pursued my way to Raleigh, and arrived there on the 23d of the month...

On Monday morning between eight and nine o'clock, while I was making ready to leave the house for the first time after my arrival, to go the store of Mr. Smith, where I was to transact my business with him, two constables, Messrs. Murray and Scott, entered, accompanied by two other men, and summoned me to appear immediately before the police. I accordingly accompanied them to the City Hall..There were a large number of people together--more than could obtain admission to the room, and a large company of mobocratic spirits crowded around the door. Mr. Loring read the writ, setting forth that I had been guilty of delivering abolition lectures in the State of Massachusetts...

"The circumstances under which I left Raleigh," said I, "are perfectly familiar to you. It is known that I had no disposition to remove from this city, but resorted to every lawful means to remain... "

Mr. Loring then whispered to some of the leading men; after which he remarked that he saw nothing in what I had done, according to my statements, implicating me in a manner worthy of notice. He called upon any present who might be in possession of information tending to disprove what I had said, or to show any wrong on my part, to produce it, otherwise I should be set at liberty. No person appeared against me; so I was discharged.

I started to leave the house; but just before I got to the door I met Mr. James Litchford, who touched me on the shoulder, and I followed him back. He observed to me that if I went out of that room I should in less than five minutes be a dead man; for there was a mob outside waiting to drink my life. Mr. Loring then spoke to me again, and said that notwithstanding I had been found guilty of nothing, yet public opinion was law; and he advised me to leave the place the next day, otherwise he was convinced I should have to suffer death...

The guard then conducted me through the mob to the prison; and I felt joyful that even a prison could protect me...

Mr. Smith now came to the prison and told me that the examination had been completed, and nothing found against me; but that it would not be safe for me to leave the prison immediately. It was agreed that I should remain in prison until after night-fall, and then steal secretly away, being let out by the keeper, and pass unnoticed to the house of my old and tried friend Mr. Boylan. Accordingly I was discharged between nine and ten o'clock.

I went by the back way leading to Mr. Boylan's; but soon and suddenly a large company of men sprang upon me, and instantly I found myself in their possession. They conducted me sometimes high above ground and sometimes dragging me along, but as silently as possible, in the direction of the gallows, which is always kept standing upon the Common, or as it is called "the pines," or "piny old field." I now expected to pass speedily into the world of spirits; I thought of that unseen region to which I seemed to be hastening; and then my mind would return to my wife and children, and the labors I had made to redeem them from bondage. Although I had the money to pay for them according to a bargain already made, it seemed to me some white man would get it, and they would die in slavery, without benefit from my exertions and the contributions of my friends. Then the thought of my own death, to occur in a few brief moments, would rush over me, and I seemed to bid adieu in spirit to all earthly things, and to hold communion already with eternity.

But at length I observed those who were carrying me away, changed their course a little from the direct line to the gallows, and hope, a faint beaming, sprung up within me; but then as they were taking me to the woods, I thought they intended to murder me there, in a place where they would be less likely to be interrupted than in so public a spot as where the gallows stood. They conducted me to a rising ground among the trees, and set me down. "Now," said they, "tell us the truth about those abolition lectures you have been giving at the North." I replied that I had related the circumstances before the court in the morning; and could only repeat what I had then said. "But that was not the truth--tell us the truth." I again said that any different story would be false, and as I supposed I was in a few minutes to die, I would not, whatever they might think I would say under other circumstances, pass into the other world with a lie upon my lips. Said one, "you were always, Lunsford, when you were here, a clever fellow, and I did not think you would be engaged in such business as giving abolition lectures." To this and similar remarks, I replied that the people of Raleigh had always said the abolitionists did not believe in buying slaves, but contended that their masters ought to free them without pay. I had been laboring to buy my family; and how then could they suppose me to be in league with the abolitionists?

After other conversation of this kind, and after they seemed to have become tired of questioning me, they held a consultation in a low whisper among themselves. Then a bucket was brought and set down by my side; but what it contained or for what it was intended, I could not divine. But soon, one of the number came forward with a pillow, and then hope sprung up, a flood of light and joy within me. The heavy weight on my heart rolled off; death had passed by and I unharmed. They commenced stripping me till every rag of clothes was removed; and then the bucket was set near, and I discovered it to contain tar.

One man, I will do him the honor to record his name, Mr. WILLIAM ANDRES, a journeyman printer, when he is any thing, except a tar-and- featherer, put his hands the first into the bucket, and was about passing them to my face. "Don't put any in his face or eyes," said one. So he desisted; but he, with three other "gentlemen," whose names I should be happy to record if I could recall them, gave me as nice a coat of tar all over, face only excepted, as any one would wish to see. Then they took the pillow and ripped it open at one end, and with the open end commenced the operation at the head and so worked downwards, of putting a coat of its contents over that of the contents of the bucket. A fine escape from the hanging this will be, thought I, provided they do not with a match set fire to the feathers. I had some fear they would. But when the work was completed they gave me my clothes, and one of them handed me my watch which he had carefully kept in his hands; they all expressed great interest in my welfare, advised me how to proceed with my business the next day, told me to stay in the place as long as I wished, and with other such words of consolation they bid me good night.

After I had returned to my family, to their inexpressible joy, as they had become greatly alarmed for my safety, some of the persons who had participated in this outrage, came in (probably influenced by a curiosity to see how the tar and feathers would be got off) and expressed great sympathy for me. They said they regretted that the affair had happened--that they had no objections to my living in Raleigh--I might feel perfectly safe to go out and transact my business preparatory to leaving--I should not be molested.

(Excerpts from pages 37-39, 41, 43-47)

On the 11th of April, it was noon with me; I left Boston on my way for Raleigh with high hopes, intending to pay over the money for my family and return with them to Boston, which I designed should be my future home; for there I had found friends, and there I would find a grave... I thought, too, that the assurances I had received from the Governor, through Mr. Smith, and the assurances of other friends, were a sufficient guaranty that I might visit the home of my boyhood, of my youth, of my manhood, in peace, especially as I was to stay but for a few days and then to return. With these thoughts, and with the thoughts of my family and freedom, I pursued my way to Raleigh, and arrived there on the 23d of the month...

On Monday morning between eight and nine o'clock, while I was making ready to leave the house for the first time after my arrival, to go the store of Mr. Smith, where I was to transact my business with him, two constables, Messrs. Murray and Scott, entered, accompanied by two other men, and summoned me to appear immediately before the police. I accordingly accompanied them to the City Hall..There were a large number of people together--more than could obtain admission to the room, and a large company of mobocratic spirits crowded around the door. Mr. Loring read the writ, setting forth that I had been guilty of delivering abolition lectures in the State of Massachusetts...

"The circumstances under which I left Raleigh," said I, "are perfectly familiar to you. It is known that I had no disposition to remove from this city, but resorted to every lawful means to remain... "

Mr. Loring then whispered to some of the leading men; after which he remarked that he saw nothing in what I had done, according to my statements, implicating me in a manner worthy of notice. He called upon any present who might be in possession of information tending to disprove what I had said, or to show any wrong on my part, to produce it, otherwise I should be set at liberty. No person appeared against me; so I was discharged.

I started to leave the house; but just before I got to the door I met Mr. James Litchford, who touched me on the shoulder, and I followed him back. He observed to me that if I went out of that room I should in less than five minutes be a dead man; for there was a mob outside waiting to drink my life. Mr. Loring then spoke to me again, and said that notwithstanding I had been found guilty of nothing, yet public opinion was law; and he advised me to leave the place the next day, otherwise he was convinced I should have to suffer death...

The guard then conducted me through the mob to the prison; and I felt joyful that even a prison could protect me...

Mr. Smith now came to the prison and told me that the examination had been completed, and nothing found against me; but that it would not be safe for me to leave the prison immediately. It was agreed that I should remain in prison until after night-fall, and then steal secretly away, being let out by the keeper, and pass unnoticed to the house of my old and tried friend Mr. Boylan. Accordingly I was discharged between nine and ten o'clock.

I went by the back way leading to Mr. Boylan's; but soon and suddenly a large company of men sprang upon me, and instantly I found myself in their possession. They conducted me sometimes high above ground and sometimes dragging me along, but as silently as possible, in the direction of the gallows, which is always kept standing upon the Common, or as it is called "the pines," or "piny old field." I now expected to pass speedily into the world of spirits; I thought of that unseen region to which I seemed to be hastening; and then my mind would return to my wife and children, and the labors I had made to redeem them from bondage. Although I had the money to pay for them according to a bargain already made, it seemed to me some white man would get it, and they would die in slavery, without benefit from my exertions and the contributions of my friends. Then the thought of my own death, to occur in a few brief moments, would rush over me, and I seemed to bid adieu in spirit to all earthly things, and to hold communion already with eternity.

But at length I observed those who were carrying me away, changed their course a little from the direct line to the gallows, and hope, a faint beaming, sprung up within me; but then as they were taking me to the woods, I thought they intended to murder me there, in a place where they would be less likely to be interrupted than in so public a spot as where the gallows stood. They conducted me to a rising ground among the trees, and set me down. "Now," said they, "tell us the truth about those abolition lectures you have been giving at the North." I replied that I had related the circumstances before the court in the morning; and could only repeat what I had then said. "But that was not the truth--tell us the truth." I again said that any different story would be false, and as I supposed I was in a few minutes to die, I would not, whatever they might think I would say under other circumstances, pass into the other world with a lie upon my lips. Said one, "you were always, Lunsford, when you were here, a clever fellow, and I did not think you would be engaged in such business as giving abolition lectures." To this and similar remarks, I replied that the people of Raleigh had always said the abolitionists did not believe in buying slaves, but contended that their masters ought to free them without pay. I had been laboring to buy my family; and how then could they suppose me to be in league with the abolitionists?

After other conversation of this kind, and after they seemed to have become tired of questioning me, they held a consultation in a low whisper among themselves. Then a bucket was brought and set down by my side; but what it contained or for what it was intended, I could not divine. But soon, one of the number came forward with a pillow, and then hope sprung up, a flood of light and joy within me. The heavy weight on my heart rolled off; death had passed by and I unharmed. They commenced stripping me till every rag of clothes was removed; and then the bucket was set near, and I discovered it to contain tar.

One man, I will do him the honor to record his name, Mr. WILLIAM ANDRES, a journeyman printer, when he is any thing, except a tar-and- featherer, put his hands the first into the bucket, and was about passing them to my face. "Don't put any in his face or eyes," said one. So he desisted; but he, with three other "gentlemen," whose names I should be happy to record if I could recall them, gave me as nice a coat of tar all over, face only excepted, as any one would wish to see. Then they took the pillow and ripped it open at one end, and with the open end commenced the operation at the head and so worked downwards, of putting a coat of its contents over that of the contents of the bucket. A fine escape from the hanging this will be, thought I, provided they do not with a match set fire to the feathers. I had some fear they would. But when the work was completed they gave me my clothes, and one of them handed me my watch which he had carefully kept in his hands; they all expressed great interest in my welfare, advised me how to proceed with my business the next day, told me to stay in the place as long as I wished, and with other such words of consolation they bid me good night.

After I had returned to my family, to their inexpressible joy, as they had become greatly alarmed for my safety, some of the persons who had participated in this outrage, came in (probably influenced by a curiosity to see how the tar and feathers would be got off) and expressed great sympathy for me. They said they regretted that the affair had happened--that they had no objections to my living in Raleigh--I might feel perfectly safe to go out and transact my business preparatory to leaving--I should not be molested.

(Excerpts from pages 37-39, 41, 43-47)

Questions for Discussion and Document Based Analysis

1. The first lines of this passage are almost poetic. From those words, what does Lunsford Lane think about his life up to that point?

2. In the third paragraph, what is the charge against Lunsford Lane that created the mobocracy?

3. Citing the text as you go, explain what happened to Lunsford Lane after he was seized by the mob.

4. How does Lunsford Lane describe his feelings during his near death experience? Cite the text.

2. In the third paragraph, what is the charge against Lunsford Lane that created the mobocracy?

3. Citing the text as you go, explain what happened to Lunsford Lane after he was seized by the mob.

4. How does Lunsford Lane describe his feelings during his near death experience? Cite the text.

Sources Referenced

James Basker, ed, American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation, (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2012), 423.

Erin Bartels, Summary of The Narrative of Lunsford Lane, Formerly of Raleigh, N.C., Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004.

Erin Bartels, Summary of The Narrative of Lunsford Lane, Formerly of Raleigh, N.C., Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004.