The Movement of Harriet Ann Jacobs

|

Harriet Ann Jacobs rocked the cultural sensibilities of her readers in the North and South after publishing her narrative entitled Incidents in the Life of Slave Girl. Jacobs grew up as an enslaved person in Edenton, North Carolina and suffered the psychological abuse and sexual advances of her owner, Dr. James Normcom. After her decision to escape her situation, Jacobs used her intellectual capacity to thwart the efforts of her master in his pursuit of his fugitive slave. While she hid in her freed grandmother's attic, Jacobs convinced Dr. Norcom that she was in the North through writing him letters. The movement and the manipulation of movement within an abusive slave institution was contingent upon Harriet Ann Jacob's literacy, which was a theme also displayed in Douglass' and Turner's narrative.

Though much of the focus of Jacob's historiography is on the expose of the sexual nature of the master and slave relationship, a careful look at her use of movement to achieve her freedom is essential to corroborate the reality that slavery created a historically unique cultural geography. |

|

|

Additionally and importantly for an examination of Jacob's movement, I followed her family papers outside of her narrative to assess her work after her manumission in aiding refugee slaves during and after the Civil War in Alexandria, Virginia. Her return to the South provides an interesting component to the reality of slave movement before and after Emancipation. There is sometimes a misconception that freed slaves desired to move to the North where attitudes towards race were more agreeable. In fact, population density maps indicate that after Emancipation, the slave population remained concentrated in the South where post war culture was exponentially more integrated under Reconstruction.

|

1. Childhood on Margaret Horniblow's Land

Narrative Excerpt(s)

"They lived together in a comfortable home; and, though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise, trusted to them for safe keeping, and liable to be demanded of them at any moment." - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 1, "Childhood," page 1

"My brother was a spirited boy; and being brought up under such influences, he early detested the name of master and mistress. One day, when his father and his mistress both happened to call him at the same time, he hesitated between the two; being perplexed to know which had the strongest claim upon his obedience. He finally concluded to go to his mistress. When my father reproved him for it, he said, "You both called me, and I didn't know which I ought to go to first."

"You are my child," replied our father, "and when I call you, you should come immediately, if you have to pass through fire and water." - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 2, "The New Master and Mistress," page 17

Context and Analysis

At the beginning of the narrative, Harriet expressed the unfortunate position of her parents. Until she was six, she lived without the knowledge of being someone else's property and lived with her mother and father in an outbuilding of Horniblow's Tavern on King Street in Edenton. Upon the death of her mother, Harriet was awakened to the reality that she was a slave. She was placed under the service of Margaret Horniblow, a sickly but kind woman in her late 20s. Upon the instant of her mother's death, Harriet's concept of family was shattered and replaced by a life where loyalty did not only lie within one's immediate family. She recorded a story of her brother being called by his owner and father at the same time as an illustration of the ways in which slavery contrived familial structures. Upon the publishing of her narrative, Jacob's brother also wrote about the family structure within slavery saying, "To be a man, and not to be a man ⎯ a father without authority ⎯ a husband and no protector ⎯ is the darkest of fates. Such was the condition of my father, and such is the condition of every slave throughout the United States: he owns nothing, he can claim nothing. His wife is not his; his children are not his; they can be taken from him and sold at any minute, as far away from each other as the human fleshmonger may see fit to carry them."

Essential Question

How did the practices of slavery confuse the concepts of family structure?

2. Margaret Horniblow & young Harriet

Narrative Excerpt(s)

"They thought she would be sure to do it, on account of my mother's love and faithful service. But, alas! we all know that the memory of a faithful slave does not avail much to save her children from the auction block.

After a brief period of suspense, the will of my mistress was read, and we learned that she had bequeathed me to her sister's daughter, a child of five years old. So vanished our hopes. My mistress had taught me the precepts of God's Word: "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself." "Whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so unto them." But I was her slave, and I suppose she did not recognize me as her neighbor. I would give much to blot out from my memory that one great wrong. As a child, I loved my mistress; and, looking back on the happy days I spent with her, I try to think with less bitterness of this act of injustice. While I was with her, she taught me to read and spell; and for this privilege, which so rarely falls to the lot of a slave, I bless her memory." - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 2, "The New Master and Mistress," page 16

Context and Analysis

When Harriet Jacobs was about twelve years old her mistress, Margaret Horniblow, passed away. Because of the service by Harriet's mother and Margaret's promise to care for Harriet, there was an expectation by the Jacobs family that Harriet would be set free in her will. Harriet would be disappointed to learn that not only was she to remain enslaved, but upon her deathbed, Margaret Horniblow suspiciously transferred Harriet's services to the three year old daughter of Dr. James Norcom. When reflecting back on this occasion decades after the fact, Harriet still spoke highly of Margaret Horniblow even though her deathbed codicil proved to be a devastating watershed moment in young Harriet's life. From that time forward, she was abused by Dr. James Norcom until her freedom.

Essential Question

What were examples of contradictions within slavery that created a sense of devotion or loyalty from enslaved people towards their owners?

3. Dr. James Norcom's Residence

Narrative Excerpt(s)

"Reader, I draw no imaginary pictures of southern homes. I am telling you the plain truth. Yet when victims make their escape from this wild beast of Slavery, northerners consent to act the part of bloodhounds, and hunt the poor fugitive back into his den, "full of dead men's bones, and all uncleanness." Nay, more, they are not only willing, but proud, to give their daughters in marriage to slaveholders. The poor girls have romantic notions of a sunny clime, and of the flowering vines that all the year round shade a happy home. To what disappointments are they destined! The young wife soon learns that the husband in whose hands she has placed her happiness pays no regard to his marriage vows. Children of every shade of complexion play with her own fair babies, and too well she knows that they are born unto him of his own household. Jealousy and hatred enter the flowery home, and it is ravaged of its loveliness...Though this bad institution deadens the moral sense, even in white women, to a fearful extent, it is not altogether extinct." - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 6, "The Jealous Mistress"

Context and Analysis

From the time she was twelve years old to the age of twenty five (1822-1835), Harriet lived under the constant physical and sexual harassment of Dr. James Norcom. Scholarship surrounding the narrative almost always highlights Jacobs' bravery in exposing the culturally taboo topic of the sexual exploitation of slaves throughout the course of her narrative. Jacob's implication was that Norcom (under the alias of Dr. Flint in the narrative) was part of a societal trend of abuse perpetrated by the slaveowning class of the South. In the introduction by the narrative's original editor, Lydia Maria Child, there are a series of statements that suggest Jacob's experience was not uncommon: " I do this for the sake of my sisters in bondage, who are suffering wrongs so foul, that our ears are too delicate to listen to them: "I do it with the hope of arousing conscientious and reflecting women at the North to a sense of their duty in the exertion of moral influence on the question of Slavery." Child's reference to "it" was Jacob's act of exposing these trends of abuse by Southerners. The appeal made by Childs and Jacobs served to infuse the North with a sense of moral obligation to respond to knowledge. Even within the text of Jacob's narrative, she accused Northerners and Northern women in particular of outstretching the geographical boundaries of slavery by being complicit in the culture that was abusing so many women.

Essential Question

How did Northerners contribute into the culture of the Southern slave system to the detriment of enslaved people?

4. Hideout: Molly Horniblow's Attic

Narrative Excerpt(s)

"A black stump, at the head of my mother's grave, was all that remained of a tree my father had planted. His grave was marked by a small wooden board, bearing his name, the letters of which were nearly obliterated. I knelt down and kissed them, and poured forth a prayer to God for guidance and support in the perilous step I was about to take. As I passed the wreck of the old meeting house, where, before Nat Turner's time, the slaves had been allowed to meet for worship, I seemed to hear my father's voice come from it, bidding me not to tarry till I reached freedom or the grave. I rushed on with renovated hopes. My trust in God had been strengthened by that prayer among the graves.

My plan was to conceal myself at the house of a friend, and remain there a few weeks till the search was over. My hope was that the doctor would get discouraged..." - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 16, Scenes at the Plantation

"Aunt Nancy brought me all the news she could hear at Dr. Flint's. From her I learned that the doctor had written to New York to a colored woman, who had been born and raised in our neighborhood, and had breathed his contaminating atmosphere. He offered her a reward if she could find out any thing about me. I know not what was the nature of her reply; but he soon after started for New York in haste, saying to his family that he had business of importance to transact. I peeped at him as he passed on his way to the steamboat. It was a satisfaction to have miles of land and water between us, even for a little while; and it was a still greater satisfaction to know that he believed me to be in the Free States. My little den seemed less dreary than it had done. He returned, as he did from his former journey to New York, without obtaining any satisfactory information. When he passed our house next morning, Benny was standing at the gate. He had heard them say that he had gone to find me, and he called out, "Dr. Flint, did you bring my mother home? I want to see her." The doctor stamped his foot at him in a rage, and exclaimed, "Get out of the way, you little damned rascal! If you don't, I'll cut off your head..." The opinion was often expressed that I was in the Free States. Very rarely did any one suggest that I might be in the vicinity. Had the least suspicion rested on my grandmother's house, it would have been burned to the ground. But it was the last place they thought of. Yet there was no place, where slavery existed, that could have afforded me so good a place of concealment." - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 21, The Loophole of Retreat

Context and Analysis

When Harriet Ann Jacobs made the bold decision to run away, she also decided to use her limited literacy and knowledge of her master's methodology in capturing slaves in order to be successful in her endeavor of escape. Jacobs decided to stay within a short walking distance from her master within the small confines of her grandmother's attic. She stayed there for nearly seven years, evading capture by sending letters to Dr. Norcom that confused him into thinking that she was in New York. Her ability to read and her practical, geographical knowledge allowed her to manipulate her master at her own great personal risk and the risk of those who were abetting her as a fugitive. Dr. Norcom would travel to New York several times to try to find her, but she was able to stay out of his grasp.

Essential Question

In what ways would literacy account for a "pathway from slavery to freedom"? How are literacy and geography contingent factors in the slave South?

5. Escape: Edenton Bay Harbor / Maritime Underground Railroad Site

Narrative Excerpt(s)

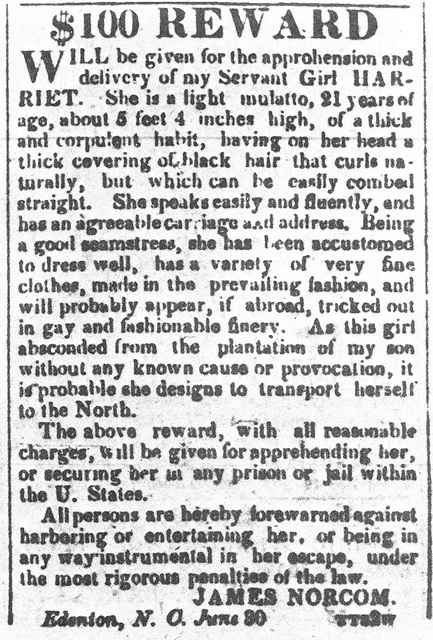

"$300 REWARD! Ran away from the subscriber, an intelligent, bright, mulatto girl, named Linda, 21 years age. Five feet four inches high. Dark eyes, and black hair inclined to curl; but it can be made straight. Has a decayed spot on a front tooth. She can read and write, and in all probability will try to get to the Free States. All persons are forbidden, under penalty of the law, to harbor or employ said slave. $150 will be given to whoever takes her in the state, and $300 if taken out of the state and delivered to me, or lodged in jail. I NEVER could tell how we reached the wharf. My brain was all of a whirl, and my limbs tottered under me. At an appointed place we met my uncle Phillip, who had started before us on a different route, that he might reach the wharf first, and give us timely warning if there was any danger. A row-boat was in readiness. As I was about to step in, I felt something pull me gently, and turning round I saw Benny, looking pale and anxious. He whispered in my ear, "I've been peeping into the doctor's window, and he's at home. Don't cry; I'll come." He hastened away. I clasped the hand of my good uncle, to whom I owed so much, and of Peter, the brave, generous friend who had volunteered to run such terrible risks to secure my safety. To this day I remember how bright his face beamed with joy, when he told me he had discovered a safe method for me to escape. Yet that intelligent, enterprising, noble-hearted man was a chattel! liable, by the laws of a country that calls itself civilized, to be sold with horses and pigs! We parted in silence. Our hearts were all too full for words! Swiftly the boat glided over the water. - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 30, Northward Bound |

Context and Analysis

After spending close to seven years in hiding within close geographical distance to Dr. Norcom, Harriet Ann Jacobs made the decision to escape into the northern United States. In doing this, Jacobs left her two children with her grandmother with the knowledge they might never be reunited. Interestingly, Jacobs made the decision to leave her children when the risk of being captured under the Fugitive Slave Law might result in the forced separation of her family. Both options were a cruel and unusual fate for enslaved people, underlining the inhumane conditions of life in slavery. During this whole period, Norcom relentlessly searched to reclaim Jacobs. She left Edenton through the Harbor and began an extraordinary journey as a traveling fugitive.

Essential Question

How did slaveholders portray their property as less than human during the era of the Slave South?

6. Fugitive: Idlewild, Nathaniel Parker Willis

Narrative Excerpt(s)

It was evident that I had no time to lose; and I hastened back to the city with a heavy heart. Again I was to be torn from a comfortable home, and all my plans for the welfare of my children were to be frustrated by that demon Slavery! I now regretted that I never told Mrs. Bruce my story. I had not concealed it merely on account of being a fugitive; that would have made her anxious, but it would have excited sympathy in her kind heart. I valued her good opinion, and I was afraid of losing it, if I told her all the particulars of my sad story. But now I felt that it was necessary for her to know how I was situated. I had once left her abruptly, without explaining the reason, and it would not be proper to do it again. I went home resolved to tell her in the morning. But the sadness of my face attracted her attention, and, in answer to her kind inquiries, I poured out my full heart to her, before bed time. She listened with true womanly sympathy, and told me she would do all she could to protect me. How my heart blessed her!

Early the next morning, Judge Vanderpool and Lawyer Hopper were consulted. They said I had better leave the city at once, as the risk would be great if the case came to trial. - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 36, The Hairbreadth Escape

Not long after my return [back from a brief trip to England], I received the following letter from Miss Emily Flint, now Mrs. Dodge:--

"In this you will recognize the hand of your friend and mistress. Having heard that you had gone with a family to Europe, I have waited to hear of your return to write to you. I should have answered the letter you wrote to me long since, but as I could not then act independently of my father, I knew there could be nothing done satisfactory to you. There were persons here who were willing to buy you and run the risk of getting you. To this I would not consent. I have always been attached to you, and would not like to see you the slave of another, or have unkind treatment. I am married now, and can protect you. My husband expects to move to Virginia this spring, where we think of settling. I am very anxious that you should come and live with me. If you are not willing to come, you may purchase yourself; but I should prefer having you live with me. If you come, you may, if you like, spend a month with your grandmother and friends, then come to me in Norfolk, Virginia. Think this over, and write as soon as possible, and let me know the conclusion. Hoping that your children are well, I remain you friend and mistress."

Of course I did not write to return thanks for this cordial invitation. I felt insulted to be thought stupid enough to be caught by such professions.

" 'Come up into my parlor,' said the spider to the fly;

''Tis the prettiest little parlor that ever you did spy.'"

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, from Chapter 38, Renewed Invitations to Go South

Context and Analysis

After Harriet entered the North, she lived in various locations and experienced the paranoia of a fugitive. She knew that Dr. Norcom was spending resources to locate and repossess his property. Eventually Jacobs found consistent work for the poet and author Nathaniel Parker Willis (Mr. Bruce in the narrative). When Willis' first wife died in child birth, Willis took Jacobs with him to England for a trip to care for the Willis child. After some time they returned to the states, Willis remarried and Jacobs went to work and live with the family at the famous Idlewild Estate. It was there that she wrote her narrative, eventually procured her freedom, and was reunited with her children. During the period between her escape from Dr. Norcom and her manumission, Dr. Norcom and his daughter (Emily Flint in the narrative) constantly contacted, harassed, and tried to convince Jacobs of her rightful place as their human property.

Essential Question

How did the Fugitive Slave Law extend the geographical boundaries of the South for fugitives?

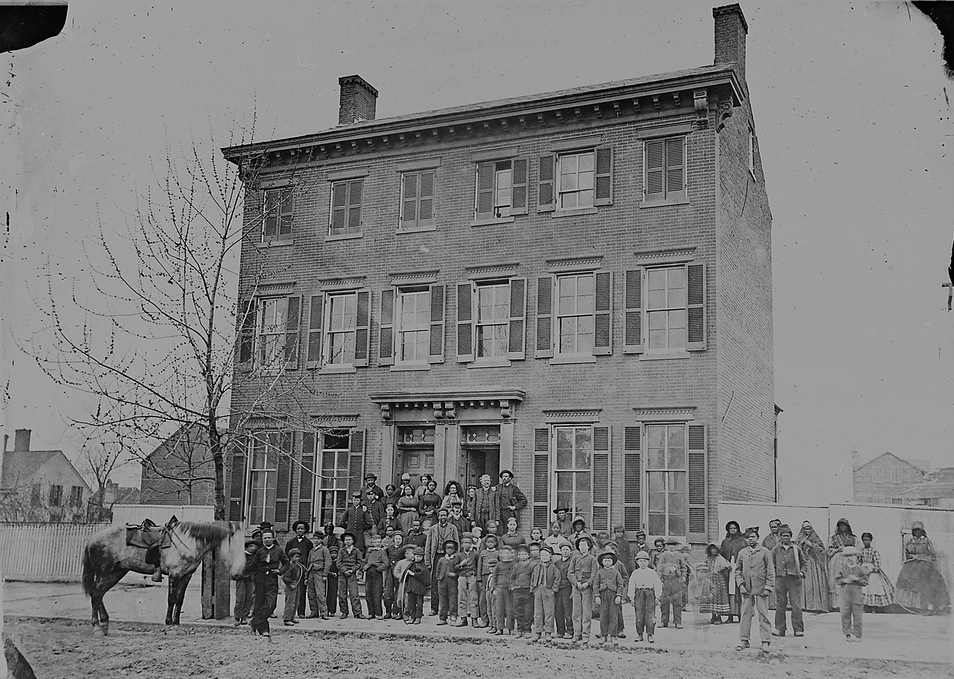

7. Home of Harriet Ann Jacobs and Julia Wilbur - Civil War Relief Work in Alexandria, VA

|

Narrative Excerpt(s)

Trust them, make them free, and give them the responsibility of caring for themselves, and they will soon learn to help each other. Some of them have been so degraded by slavery that they do not know the usages of civilized life: they know little else than the handle of the hoe, the plough, the cotton pad, and the overseer's lash. Have patience with them. You have helped to make them what they are; teach them civilization. You owe it to them, and you will find them as apt to learn as any other people that come to you stupid from oppression. The negroes' strong attachment no one doubts; the only difficulty is, they have cherished it too strongly. - "Life Among the Contrabands," Harriet A. Jacobs, from The Liberator, September 5, 1862 |

Context and Analysis

After her manumission, the publishing of her narrative, the start of the Civil War, and Lincoln's issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation, Harriet Ann Jacobs took on a job as a reporter for The Liberator under William Lloyd Garrison. After this, she moved into the South to take on Relief Work in Alexandria, Virginia. It is hard not to emphasize the significance of this transition. Jacobs was a free woman and was employed, made famous by her narrative, and then travelled back into a war torn and dangerous South in order to assist newly emancipated enslaved people as they attempted to make sense of the task. Her documentation in letters and published articles of the conditions of refugees in Alexandria revealed the staggering nature of work which she undertook. She enlisted the help of Northerners and worked closely with Julia Wilbur to provide basic relief to the refugee African Americans in Alexandria, Virginia. In 1865, Jacobs revisited her hometown of Edenton and recorded seeing the son of her former master who, "lost all his property, and professes to have been all through the war a good Union man, and a great friend of the negro. He asks the influence of his former slave to procure him an office under the Freedmen's Bureau." One can only imagine Jacob's response to the son of the man who had caused so much personal pain.

Essential Questions

Why would a freed person who lived in the North return to the South during the Civil War and after the war?

8. Jacobs Free School - Relief Work through Educational Reform

Narrative Excerpt(s)

"A word about the schools. It is pleasant to see that eager group of old and young, striving to learn their A, B, C, and Scripture sentences. Their great desire is to learn to read. While in the school-room, I could not but feel how much these young women and children needed female teachers who could do something more than teach them their A, B, C. They need to be taught the right habits of living and the true principles of life." - "Life Among the Contrabands," Harriet A. Jacobs, from The Liberator, September 5, 1862

"… I found the School house not finished for the want of funds I also found many missionary applicants waiting to take charge of the School. I thought it best to wait and see what was the disposition of the Freedmen to whom the Building belonged. My daughter came here to assist me in my labors after visiting many families she was desirous to open a school, with Virginia she gathered the children in their different homes & taught them, the week before the School room was finished I called on one of the colored Trustees, stated the object of bringing the young ladies to Alexandria. he said he would be proud to have the ladies teach in their school, but the white people had made all the arrangements without consulting them... I do not object to a white teacher but I think it has a good effect upon these people to convince them their own race can do something for their Elevation it inspires them with confidence to help each other." - Letter from Harriet Ann Jacobs to Hannah Stevenson, Alex., March 10, 1864

Context and Analysis

The Jacobs Free School opened on January 11, 1864 in Alexandria. Like most newly constructed schools designed for the refugee African American population, the school faced many obstacles. Jacobs needed to find teachers and funding, but also had to struggle to establish black efficacy in the South, which meant facing the structural and historic racism that defined relationships between black and white Americans. Jacobs helped organize the local community to raise additional funds and to direct further selection of teachers because she was determined to create a school administered by the people it sought to serve. By the end of the Civil War, Jacobs had transformed her existence from abused, enslaved, and imprisoned into a role of leadership and revolutionary reform in the American South.

Essential Question

What challenges were faced by emancipated slaves in regards to their education?

Sources Referenced

Digital Scholarship Lab of the University of Richmond. "Voting America." Accessed on March 28, 2015.

Jacobs, John. “A True Tale of Slavery.” The Leisure Hour: A Family Journal of Instruction and Recreation. February 7, 1861.

"Report of Harriet Ann Jacob's visit to Edenton, N.C." The Freedmen's Record. December 1865, p. 199-200. Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004.

Yellin, Jean Fagan. Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004.

Yellin, Jean Fagan, ed. "The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers." The University of North Carolina Press.

Jacobs, John. “A True Tale of Slavery.” The Leisure Hour: A Family Journal of Instruction and Recreation. February 7, 1861.

"Report of Harriet Ann Jacob's visit to Edenton, N.C." The Freedmen's Record. December 1865, p. 199-200. Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004.

Yellin, Jean Fagan. Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004.

Yellin, Jean Fagan, ed. "The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers." The University of North Carolina Press.