Introduction and Context

When I got on the Canada side, on the morning of the 28th of October, 1830, my first impulse was to throw myself on the ground, and giving way to the riotous exultation of my feelings, to execute sundry antics which excited the astonishment of those who were looking on. A gentleman of the neighborhood, Colonel Warren, who happened to be present, thought I was in a fit, and as he inquired what was the matter with the poor fellow, I jumped up and told him I was free. "O," said he, with a hearty laugh, "is that it? I never knew freedom make a man roll in the sand before." - Josiah Henson, p. 58-59

|

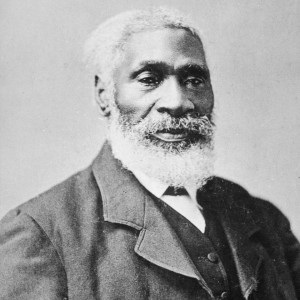

Josiah Henson was born in Maryland in 1793. According to Henson's narrative, his mother and father had six children but his memories of his father are few. Henson's father was sold after an incident when he threatened to beat a slave overseer for his treatment of Josiah's mother and his wife. Josiah, as a young boy, remembered the brutal punishment of his father - his ear was cut off, his back was whipped and he had a severe cut to his head. Soon after this, his father was gone.

Following that trauma, his mother and his siblings were resettled under the ownership of Doctor McPherson, who had a reputation for the kind treatment of his slaves. Unfortunately, after the death of McPherson, Henson's family was split up and sold among McPherson's heirs. Josiah was initially separated from his mother, but was fortunately reunited when Josiah became sick and needed his mother to care for him. |

When he was reunited with his mother, he was under the ownership of Issac Riley who he determined as, "vulgar in his habits, unprincipled and cruel." Henson worked as a water boy and eventually as a field hand. The passage below describes the basic and general conditions of slaves and how they lived on a day to day basis. As he became older and more developed, Henson gained the job of accompanying his master to town as he would socialize.

Isaac Riley notoriously outlived his means and was eventually forced to sell some of his slaves to pay off debts. Josiah Henson was then sold to Amos Riley, Isaac's brother, in Kentucky. Working under Amos Riley, Henson desired to purchase his freedom. Encouraged by a white Methodist minister, Henson obtained permission to travel to Maryland and visit his old master and raised money by preaching on the journey.

Isaac Riley welcomed Henson's visit and negotiated a price for manumission (purchasing his freedom) but was surprised and impressed by Henson's accumulated earnings. He agreed to a price of four-hundred and fifty dollars and took Henson's cash earnings of three-hundred and fifty dollars as a down payment. Unfortunately, he tricked the unsuspecting Henson by promising to forward the manumission papers to Amos Riley on his behalf, and then sent a letter that raised the agreed price to one thousand dollars.

Henson learned about this on his return to Kentucky and was devastated. The despair was deepened by Amos Riley's decision to sell Henson south. On the trip, Amos' son (also the overseer for the trip), fell ill and Henson returned him to his master. When Amos Riley was not grateful and still wanted to sell Henson, Josiah decided to escape with his wife and four children. They walked through the cold all the way from Kentucky to Buffalo, New York.

Famously, Henson's life and story written in his narrative became the inspiration for the transformative cultural novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Isaac Riley notoriously outlived his means and was eventually forced to sell some of his slaves to pay off debts. Josiah Henson was then sold to Amos Riley, Isaac's brother, in Kentucky. Working under Amos Riley, Henson desired to purchase his freedom. Encouraged by a white Methodist minister, Henson obtained permission to travel to Maryland and visit his old master and raised money by preaching on the journey.

Isaac Riley welcomed Henson's visit and negotiated a price for manumission (purchasing his freedom) but was surprised and impressed by Henson's accumulated earnings. He agreed to a price of four-hundred and fifty dollars and took Henson's cash earnings of three-hundred and fifty dollars as a down payment. Unfortunately, he tricked the unsuspecting Henson by promising to forward the manumission papers to Amos Riley on his behalf, and then sent a letter that raised the agreed price to one thousand dollars.

Henson learned about this on his return to Kentucky and was devastated. The despair was deepened by Amos Riley's decision to sell Henson south. On the trip, Amos' son (also the overseer for the trip), fell ill and Henson returned him to his master. When Amos Riley was not grateful and still wanted to sell Henson, Josiah decided to escape with his wife and four children. They walked through the cold all the way from Kentucky to Buffalo, New York.

Famously, Henson's life and story written in his narrative became the inspiration for the transformative cultural novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Document - Josiah Henson, from The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada

The character of R., the master whom I faithfully served for many years, is by no means an uncommon one in any part of the world; but it is to be regretted that a domestic institution should anywhere put it in the power of such a one to tyrannize over his fellow beings, and inflict so much needless misery as is sure to be produced by such a man in such a position. Coarse and vulgar in his habits, unprincipled and cruel in his general deportment, and especially addicted to the vice of licentiousness, his slaves had little opportunity for relaxation from wearying labor, were supplied with the scantiest means of sustaining their toil by necessary food, and had no security for personal rights. The natural tendency of slavery is, to convert the master into a tyrant, and the slave into the cringing, treacherous, false, and thieving victim of tyranny. R. and his slaves were no exception to the general rule, but might be cited as apt illustrations of the nature of the case.

My earliest employments were, to carry buckets of water to the men at work, to hold a horse-plough, used for weeding between the rows of corn, and as I grew older and taller, to take care of master's saddle-horse. Then a hoe was put into my hands, and I was soon required to do the day's work of a man; and it was not long before I could do it, at least as well as my associates in misery.

The every-day life of a slave on one of our southern plantations, however frequently it may have been described, is generally little known at the North; and must be mentioned as a necessary illustration of the character and habits of the slave and the slave-holder, created and perpetuated by their relative position. The principal food of those upon my master's plantation consisted of corn meal, and salt herrings; to which was added in summer a little buttermilk, and the few vegetables which each might raise for himself and his family, on the little piece of ground which was assigned to him for the purpose, called a truck patch.

The meals were two, daily. The first, or breakfast, was taken at 12 o'clock, after laboring from daylight; and the other when the work of the remainder of the day was over. The only dress was of tow cloth, which for the young, and often even for those who had passed the period of childhood, consisted of a single garment, something like a shirt, but longer, reaching to the ancles; and for the older, a pair of pantaloons, or a gown, according to the sex; while some kind of round jacket, or overcoat, might be added in winter, a wool hat once in two or three years, for the males, and a pair of coarse shoes once a year. Our lodging was in log huts, of a single small room, with no other floor than the trodden earth, in which ten or a dozen persons--men, women, and children--might sleep, but which could not protect them from dampness and cold, nor permit the existence of the common decencies of life. There were neither beds, nor furniture of any description--a blanket being the only addition to the dress of the day for protection from the chillness of the air or the earth. In these hovels were we penned at night, and fed by day; here were the children born, and the sick--neglected. Such were the provisions for the daily toil of the slave.

Notwithstanding this system of management, however, I grew to be a robust and vigorous lad, and at fifteen years of age, there were few who could compete with me in work, or in sport--for not even the condition of a slave can altogether repress the animal spirits of the young negro. I was competent to all the work that was done upon the farm, and could run faster and farther, wrestle longer, and jump higher, than anybody about me. My master and my fellow slaves used to look upon me, and speak of me, as a wonderfully smart fellow, and prophecy the great things I should do when I became a man.

A casual word of this sort, sometimes overheard, would fill me with a pride and ambition which some would think impossible in a negro slave, degraded, starved, and abused as I was, and had been, from my earliest recollection. But the love of superiority is not confined to kings and emperors; and it is a positive fact, that pride and ambition were as active in my soul as probably they ever were in that of the greatest soldier or statesman. The objects I pursued, I must admit, were not just the same as theirs. Mine were to be first in the field, whether we were hoeing, mowing, or reaping; to surpass those of my own age, or indeed any age, in athletic exercises; and to obtain, if possible, the favorable regard of the petty despot who ruled over us. This last was an exercise of the understanding, rather than of the affections; and I was guided in it more by what I supposed would be effectual, than by a nice judgment of the propriety of the means I used.

I obtained great influence with my companions, as well by the superiority I showed in labor and in sport, as by the assistance I yielded them, and the favors I conferred upon them, from impulses which I cannot consider as wrong, though it was necessary for me to conceal sometimes the act as well as its motive. I have toiled, and induced others to toil, many an extra hour, in order to show my master what an excellent day's work had been accomplished, and to win a kind word, or a benevolent deed from his callous heart.

(excerpt, p. 5-9)

My earliest employments were, to carry buckets of water to the men at work, to hold a horse-plough, used for weeding between the rows of corn, and as I grew older and taller, to take care of master's saddle-horse. Then a hoe was put into my hands, and I was soon required to do the day's work of a man; and it was not long before I could do it, at least as well as my associates in misery.

The every-day life of a slave on one of our southern plantations, however frequently it may have been described, is generally little known at the North; and must be mentioned as a necessary illustration of the character and habits of the slave and the slave-holder, created and perpetuated by their relative position. The principal food of those upon my master's plantation consisted of corn meal, and salt herrings; to which was added in summer a little buttermilk, and the few vegetables which each might raise for himself and his family, on the little piece of ground which was assigned to him for the purpose, called a truck patch.

The meals were two, daily. The first, or breakfast, was taken at 12 o'clock, after laboring from daylight; and the other when the work of the remainder of the day was over. The only dress was of tow cloth, which for the young, and often even for those who had passed the period of childhood, consisted of a single garment, something like a shirt, but longer, reaching to the ancles; and for the older, a pair of pantaloons, or a gown, according to the sex; while some kind of round jacket, or overcoat, might be added in winter, a wool hat once in two or three years, for the males, and a pair of coarse shoes once a year. Our lodging was in log huts, of a single small room, with no other floor than the trodden earth, in which ten or a dozen persons--men, women, and children--might sleep, but which could not protect them from dampness and cold, nor permit the existence of the common decencies of life. There were neither beds, nor furniture of any description--a blanket being the only addition to the dress of the day for protection from the chillness of the air or the earth. In these hovels were we penned at night, and fed by day; here were the children born, and the sick--neglected. Such were the provisions for the daily toil of the slave.

Notwithstanding this system of management, however, I grew to be a robust and vigorous lad, and at fifteen years of age, there were few who could compete with me in work, or in sport--for not even the condition of a slave can altogether repress the animal spirits of the young negro. I was competent to all the work that was done upon the farm, and could run faster and farther, wrestle longer, and jump higher, than anybody about me. My master and my fellow slaves used to look upon me, and speak of me, as a wonderfully smart fellow, and prophecy the great things I should do when I became a man.

A casual word of this sort, sometimes overheard, would fill me with a pride and ambition which some would think impossible in a negro slave, degraded, starved, and abused as I was, and had been, from my earliest recollection. But the love of superiority is not confined to kings and emperors; and it is a positive fact, that pride and ambition were as active in my soul as probably they ever were in that of the greatest soldier or statesman. The objects I pursued, I must admit, were not just the same as theirs. Mine were to be first in the field, whether we were hoeing, mowing, or reaping; to surpass those of my own age, or indeed any age, in athletic exercises; and to obtain, if possible, the favorable regard of the petty despot who ruled over us. This last was an exercise of the understanding, rather than of the affections; and I was guided in it more by what I supposed would be effectual, than by a nice judgment of the propriety of the means I used.

I obtained great influence with my companions, as well by the superiority I showed in labor and in sport, as by the assistance I yielded them, and the favors I conferred upon them, from impulses which I cannot consider as wrong, though it was necessary for me to conceal sometimes the act as well as its motive. I have toiled, and induced others to toil, many an extra hour, in order to show my master what an excellent day's work had been accomplished, and to win a kind word, or a benevolent deed from his callous heart.

(excerpt, p. 5-9)

Questions for Discussion and Document Based Analysis

- According to the text, what is the "natural tendency" of the nature of the slave institution?

- Based on your answer for the first question, how is life at R.'s plantation an illustration of the nature of slavery?

- How did Josiah Henson seek to be "superior"?

Finding Josiah Henson - Archaeological Dig

|

Time Team America traveled to an upscale DC suburb to try to answer some big questions. Much of Henson’s influential memoir was written about his time at the Riley Plantation, his role while there, and his subsequent escape. With Henson’s own account as inspiration, the archeological team wanted to see if they could help find evidence that linked the modern landscape with the early nineteenth century plantation where Henson worked.

Questions to be answered by archaelogists:

|

Sources Referenced

W. B. Hartgrove, The Story of Josiah Henson, The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Jan., 1918): 1-21.

Stephen Railton, ed., "Josiah Henson's Life," Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture, University of Virginia, Accessed on November 1, 2014.

Stephen Railton, ed., "Josiah Henson's Life," Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture, University of Virginia, Accessed on November 1, 2014.