Introduction and Context

My readers will be delighted to learn that Frederick Douglass—the fugitive slave—has at last concluded his narrative. All who know the wonderful gifts of friend Douglass know that his narrative must, in the nature of things, be written with great power. It is so indeed. It is the most thrilling work which the American press ever issued--and the most important. If it does not open the eyes of this people, they must be petrified into eternal sleep. - Lynn Pioneer, A Review of the Narrative of Frederick Douglass published in The Liberator on May 30, 1845

|

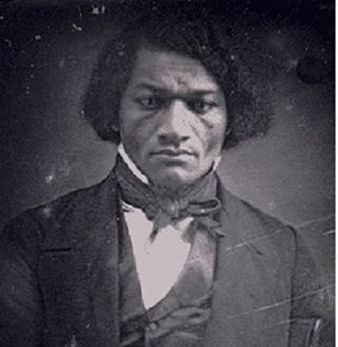

By most accounts, Frederick Douglass is the most acclaimed writer in the African-American literary tradition. For example, the autobiography excerpted in this anthology was the best selling and most widely read amongst the slave narrative genre. Douglass became a prolific writer and worked over his life to expand his original narrative and produce other works.

In February of 1818, Frederick Douglass was born in Maryland to a black mother and an unknown white man. Most of his childhood was spent with his grandparents and an aunt, seeing his mother only four or five times before her death when he was seven. As a young boy, he witnessed many severe beatings and whippings while he lived with Colonel Edward Lloyd. His narrative is full of insistence that his experience was not unique, but rather was an "every man" slave narrative. Arguably, the "shared narrative" theme is the feature of the autobiography that made it so compelling: if this was the common experience of the slave, then a change was necessary in America, according to Douglass' argument. |

Douglass' narrative displayed a progression from complete bondage to liberty, and used his experience to show how freedom created a new identity for him. At seven years old, Douglass was sent to work for Hugh Auld, a ship carpenter in Baltimore. During this time, he learned to read and write and was exposed to the philosophy of abolitionists. In the city, he found increased autonomy due to the help of Auld's wife, Sophia, who helped him through his journey towards literacy. Auld soon put a stop to his desires for freedom by hiring him out to other slave owners and putting Douglass to more difficult slave work. However, the shift had the opposite effect on Douglass and only served to inspire him to escape life as a slave.

In Douglass' 1845 Narrative, Douglass did not include the details of his escape because he was concerned that if he revealed his means of escape that it would put other slaves who wanted to escape at danger. It wasn't until later versions that he mentioned his escape.

In Douglass' 1845 Narrative, Douglass did not include the details of his escape because he was concerned that if he revealed his means of escape that it would put other slaves who wanted to escape at danger. It wasn't until later versions that he mentioned his escape.

Document - from the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself.

I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit...

...The slaves selected to go to the Great House Farm, for the monthly allowance for themselves and their fellow-slaves, were peculiarly enthusiastic. While on their way, they would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness. They would compose and sing as they went along, consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up, came out--if not in the word, in the sound; --and as frequently in the one as in the other. They would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone. Into all of their songs they would manage to weave something of the Great House Farm. Especially would they do this, when leaving home. They would then sing most exultingly the following words:--

"I am going away to the Great House Farm!

O, yea! O, yea! O!"

This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.

I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. The mere recurrence to those songs, even now, afflicts me; and while I am writing these lines, an expression of feeling has already found its way down my cheek. To those songs I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds. If any one wishes to be impressed with the soul-killing effects of slavery, let him go to Colonel Lloyd's plantation, and, on allowance-day, place himself in the deep pine woods, and there let him, in silence, analyze the sounds that shall pass through the chambers of his soul,--and if he is not thus impressed, it will only be because "there is no flesh in his obdurate heart."

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.

(excerpt from Chapter 1, p. 1 and Chapter 2, p. 13-15)

...The slaves selected to go to the Great House Farm, for the monthly allowance for themselves and their fellow-slaves, were peculiarly enthusiastic. While on their way, they would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness. They would compose and sing as they went along, consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up, came out--if not in the word, in the sound; --and as frequently in the one as in the other. They would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone. Into all of their songs they would manage to weave something of the Great House Farm. Especially would they do this, when leaving home. They would then sing most exultingly the following words:--

"I am going away to the Great House Farm!

O, yea! O, yea! O!"

This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.

I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. The mere recurrence to those songs, even now, afflicts me; and while I am writing these lines, an expression of feeling has already found its way down my cheek. To those songs I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds. If any one wishes to be impressed with the soul-killing effects of slavery, let him go to Colonel Lloyd's plantation, and, on allowance-day, place himself in the deep pine woods, and there let him, in silence, analyze the sounds that shall pass through the chambers of his soul,--and if he is not thus impressed, it will only be because "there is no flesh in his obdurate heart."

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.

(excerpt from Chapter 1, p. 1 and Chapter 2, p. 13-15)

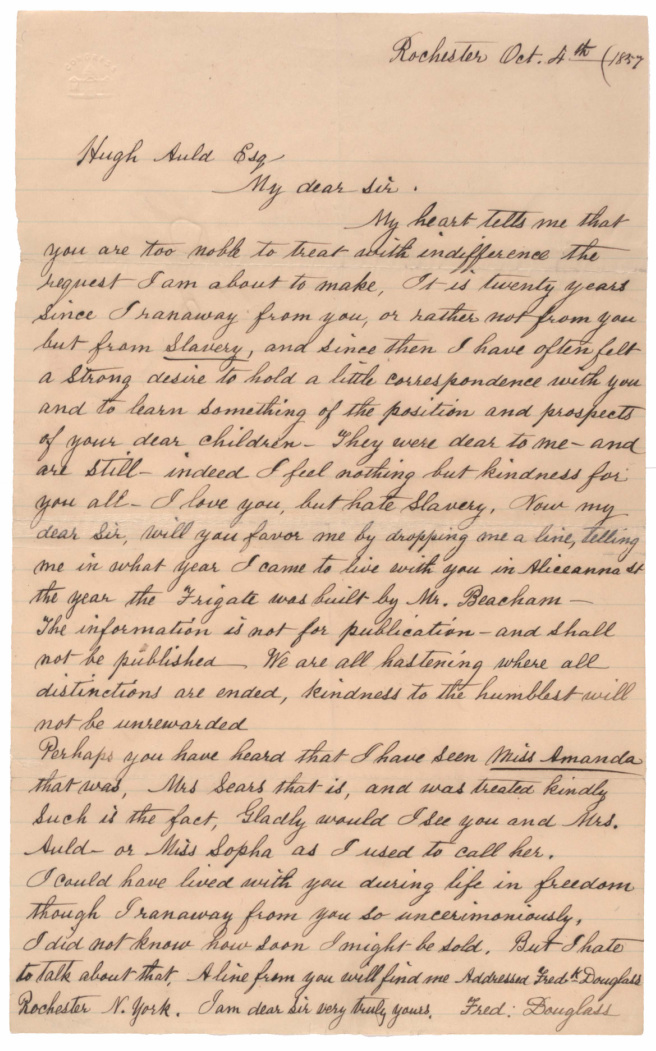

Additional Document - Letter from Frederick Douglass to his former owner, Hugh Auld, 1857

Questions for Discussion and Document Based Analysis

- According to the text, when was Frederick Douglass born?

- How does Frederick Douglass describe the songs of slaves? Why is this important?

- How does Douglass reflect on the songs after he gains his freedom?

Sources Referenced

Mark K. Burns, "A Slave in Form but Not in Fact": Subversive Humor and the Rhetoric of Irony in "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," Studies in American Humor, New Series 3, No. 12 (2005): 83-96.

María del Mar Gallego Durán, "Writing As Self-Creation: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," Atlantis, Vol. 16, No. 1/2 (November 1994):119-132.

María del Mar Gallego Durán, "Writing As Self-Creation: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," Atlantis, Vol. 16, No. 1/2 (November 1994):119-132.